Britta Lumer & Eduardo Chillida. The evening moves on slowly, and I, gazing, want to see.

2 July to 4 September 2021 ⟶ Showroom

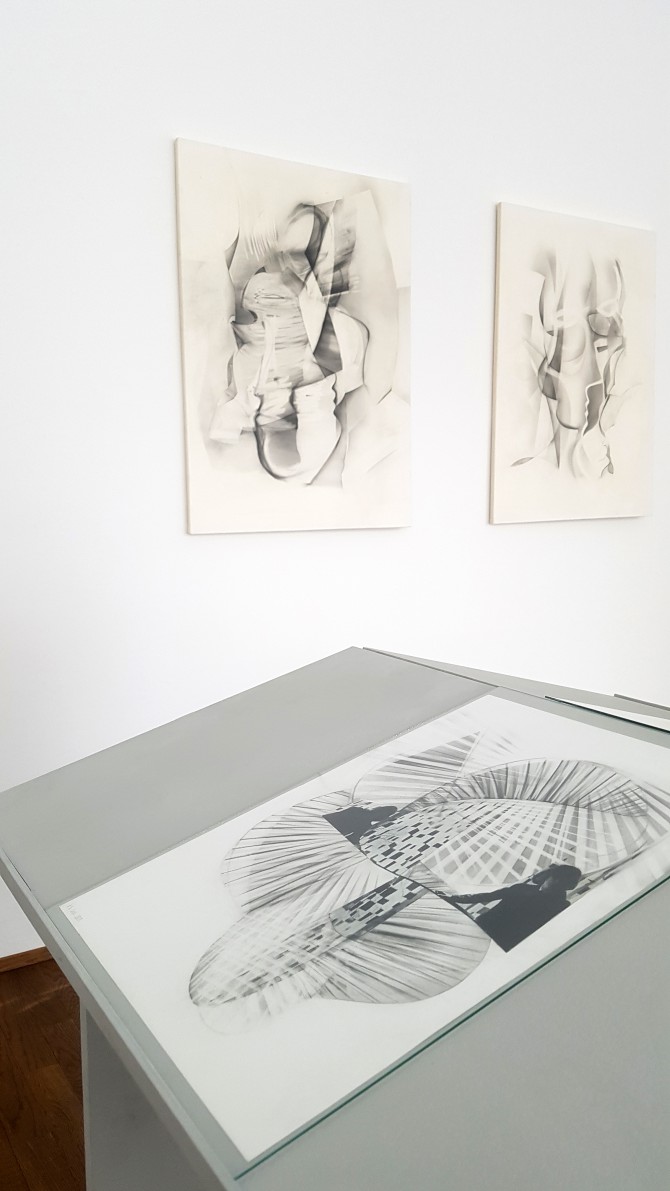

Installation view, Showroom Galerie Georg Nothelfer

Installation view, Showroom Galerie Georg Nothelfer

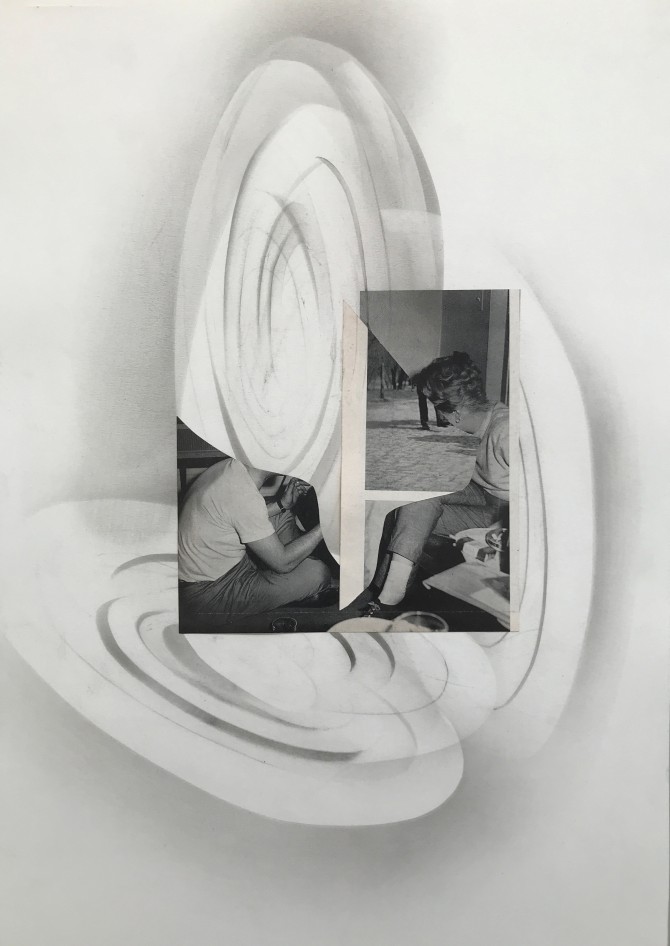

Britta Lumer, 2020, 03. October 2020 (101), Collage, Charcoal on Paper 42 x 29,7 cm

Britta Lumer, 2020, 03. October 2020 (101), Collage, Charcoal on Paper 42 x 29,7 cm

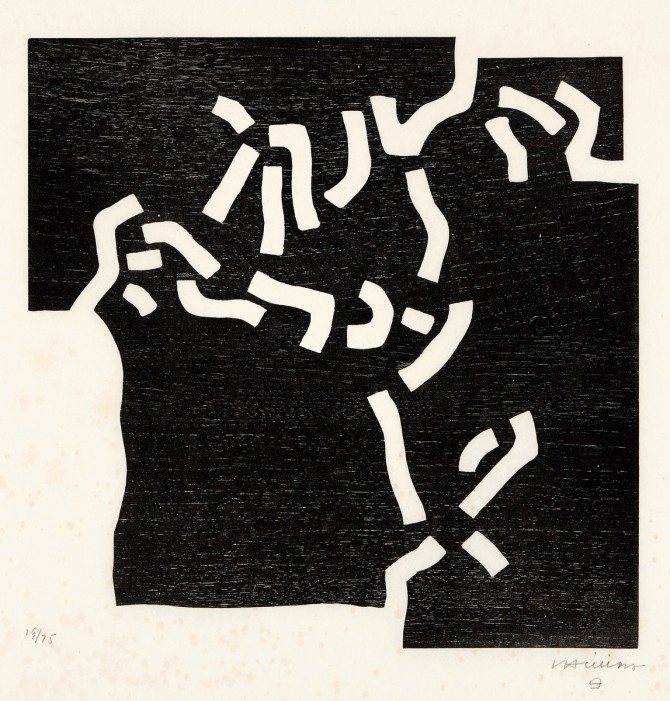

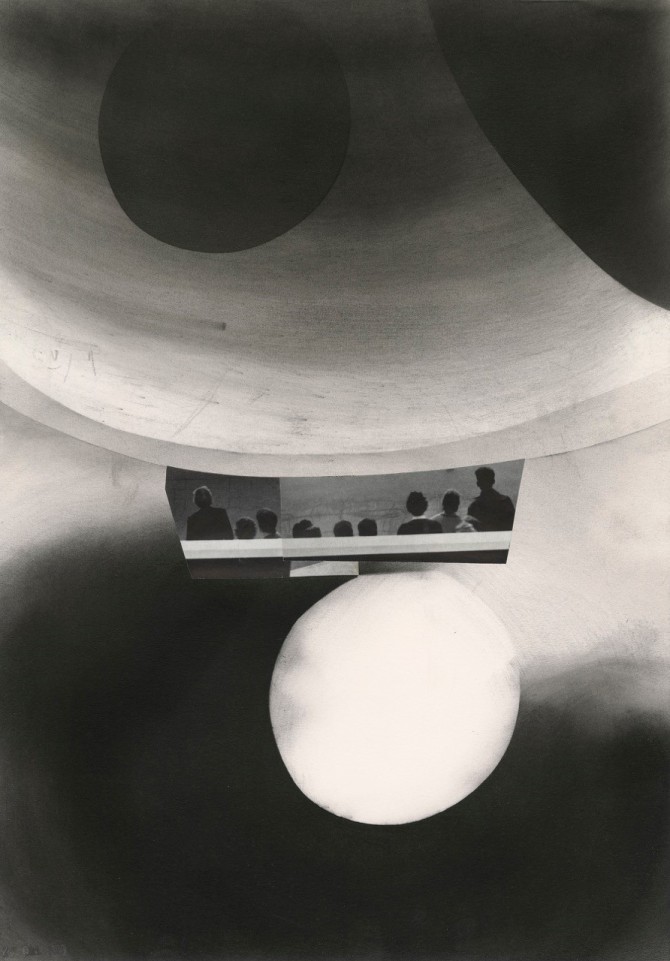

Eduardo Chillida, 1969, Beltza II, Ed.51/75, Woodcut on japanese Paper, 63,5 x 94,5 cm (WV69005)

Eduardo Chillida, 1969, Beltza II, Ed.51/75, Woodcut on japanese Paper, 63,5 x 94,5 cm (WV69005)

Installation view Showroom Galerie Georg Nothelfer

Installation view Showroom Galerie Georg Nothelfer

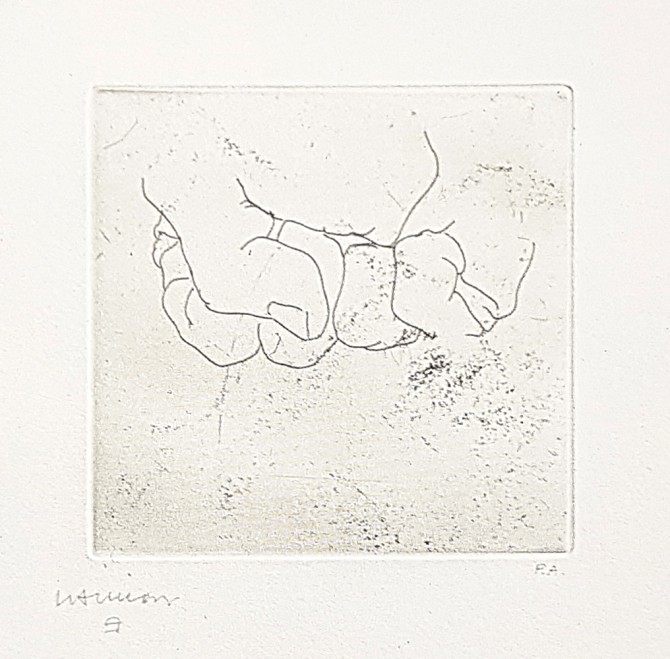

Eduardo Chillida, 1979, Esku XII, Edition 15/50, Etching, Rives BFK, 48 x 38,5 cm (WV 73007)

Eduardo Chillida, 1979, Esku XII, Edition 15/50, Etching, Rives BFK, 48 x 38,5 cm (WV 73007)

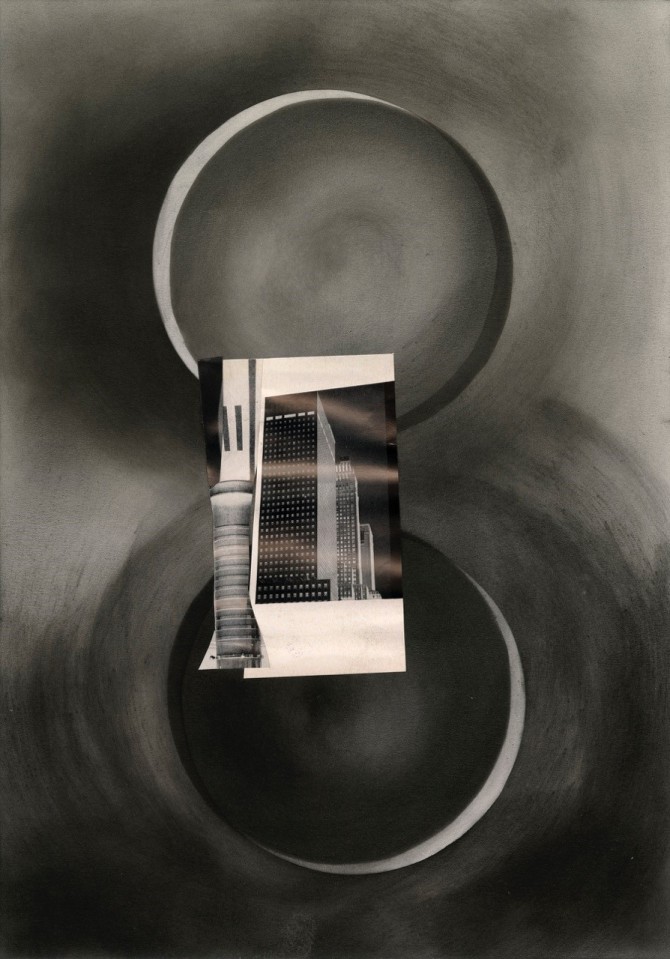

Britta Lumer, 2020, 11. October 2020 (055), Collage, Carcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Britta Lumer, 2020, 11. October 2020 (055), Collage, Carcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

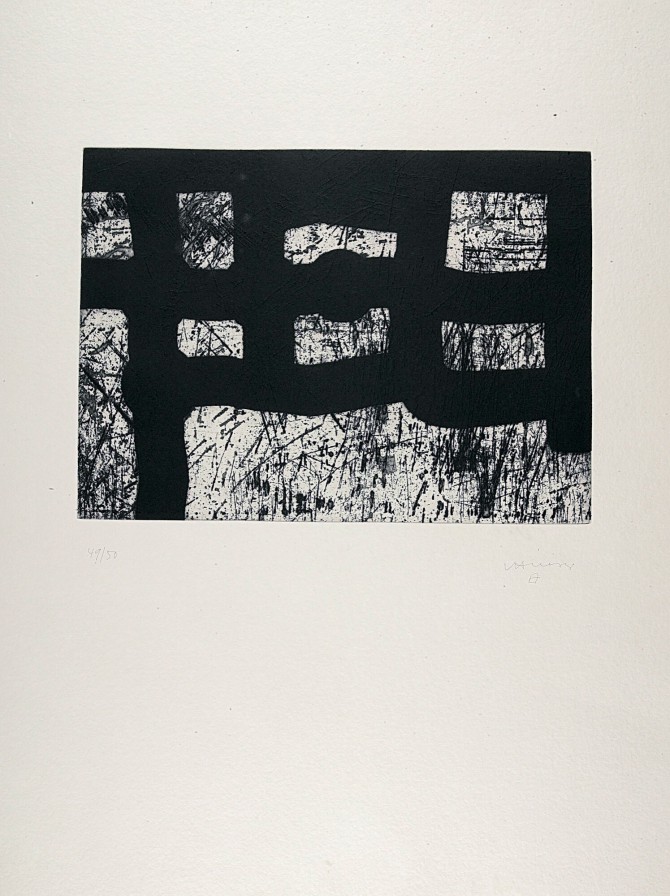

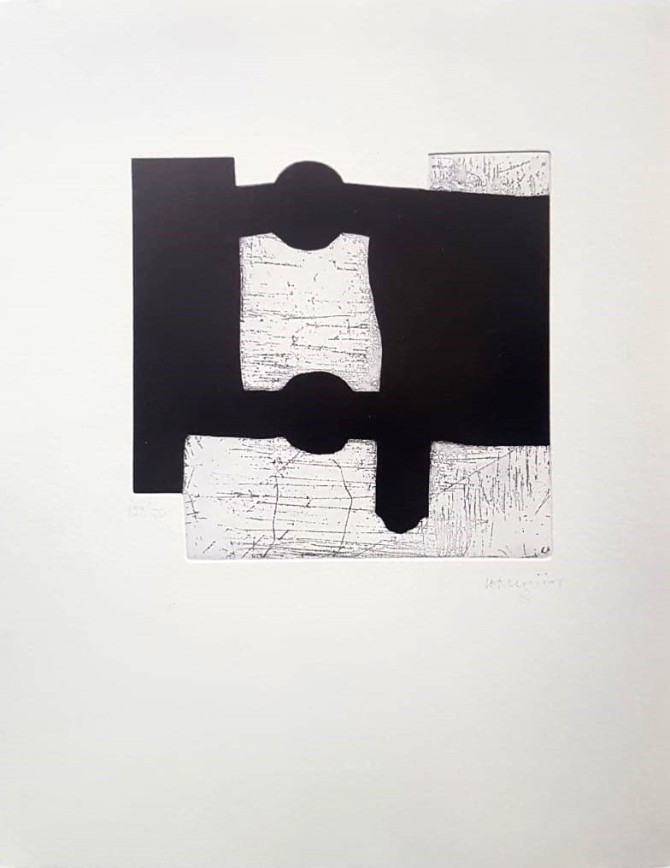

Eduardo Chillida, 1997, Lagunkide, Edition H.C.1/15, Aquatinta Etching, Esculan gris, 80,5 x 61 cm (WV97014)

Eduardo Chillida, 1997, Lagunkide, Edition H.C.1/15, Aquatinta Etching, Esculan gris, 80,5 x 61 cm (WV97014)

Installation view Showroom Galerie Georg Nothelfer

Installation view Showroom Galerie Georg Nothelfer

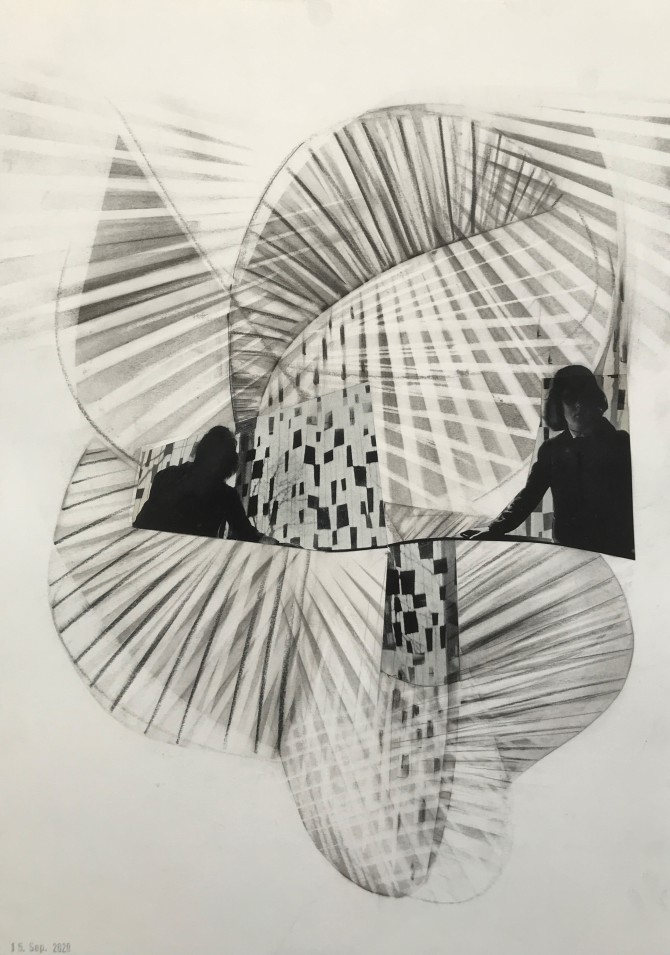

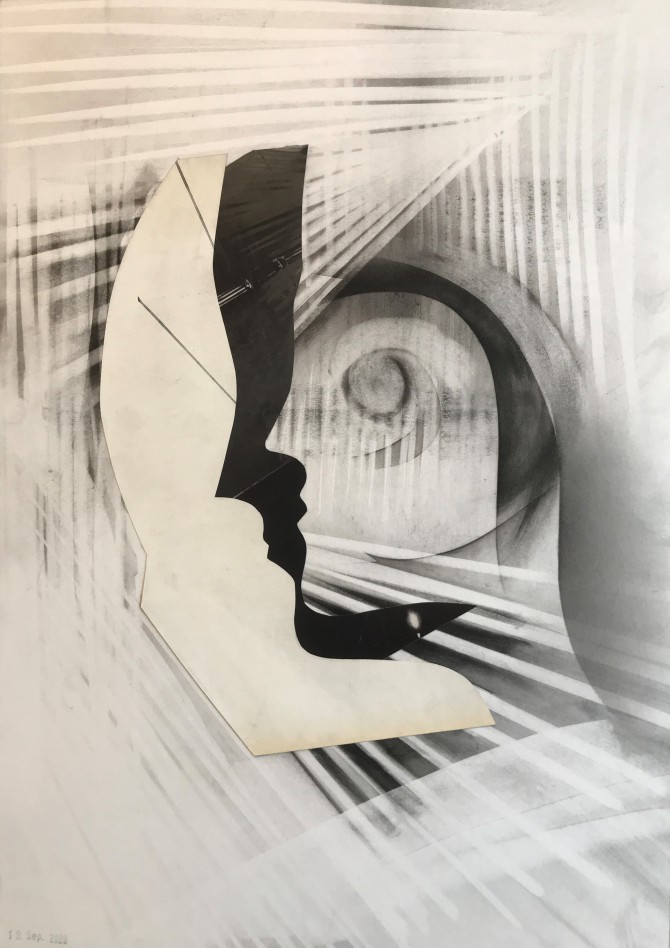

Britta Lumer, 2020, 15. September 2020 (100), Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Britta Lumer, 2020, 15. September 2020 (100), Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

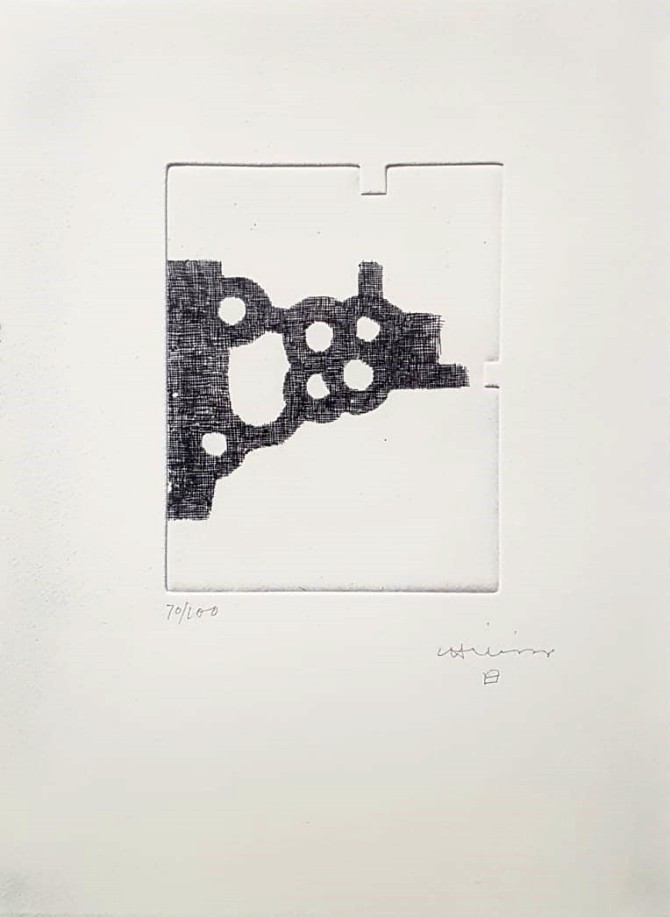

Eduardo Chillida, 1997, Jorge Semprún: L'Ecriture ou la vie, Aquatinta Etching, Arches BFK for the Book with texts by Jorges Semprún, Edition 36/100, 38 x 28 cm (WV970179)

Eduardo Chillida, 1997, Jorge Semprún: L'Ecriture ou la vie, Aquatinta Etching, Arches BFK for the Book with texts by Jorges Semprún, Edition 36/100, 38 x 28 cm (WV970179)

Installation view Showroom Galerie Georg Nothelfer

Installation view Showroom Galerie Georg Nothelfer

Britta Lumer, 2020, 30. October 2020 (023), Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Britta Lumer, 2020, 30. October 2020 (023), Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Eduardo Chillida, 2000, Untitled (from Aromas) Etching, Edition 57/120, 53,5 x 42,5 cm (WV00007) (SOLD)

Eduardo Chillida, 2000, Untitled (from Aromas) Etching, Edition 57/120, 53,5 x 42,5 cm (WV00007) (SOLD)

Installation view Showroom Galerie Georg Nothelfer

Installation view Showroom Galerie Georg Nothelfer

Britta Lumer, 2020, 06. November 2020 (025), Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Britta Lumer, 2020, 06. November 2020 (025), Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

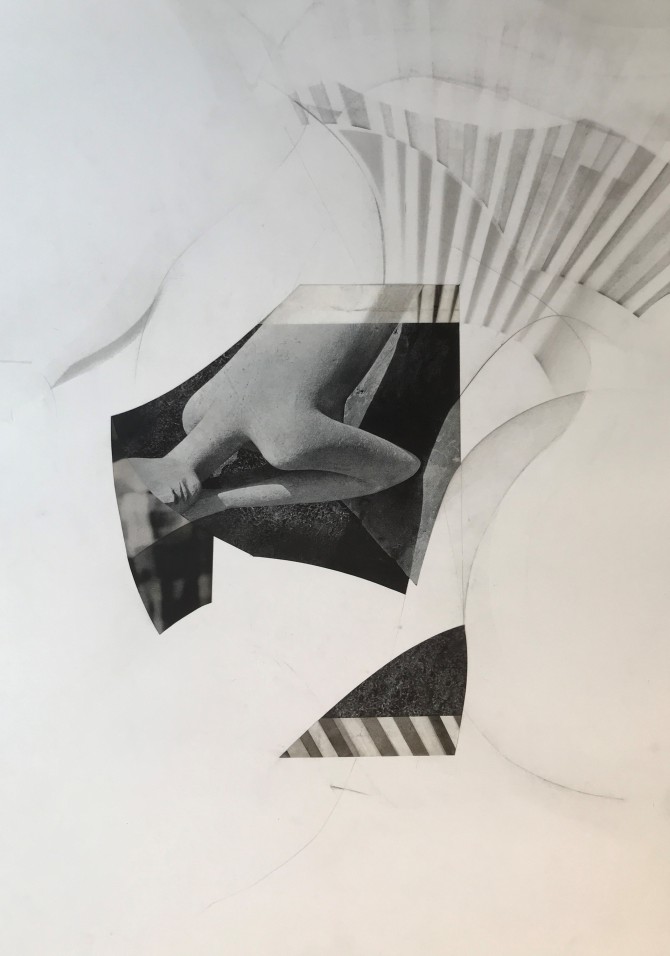

Britta Lumer, 2020, 20. September 2020 (046), Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Britta Lumer, 2020, 20. September 2020 (046), Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Installation view Showroom Galerie Georg Nothelfer

Installation view Showroom Galerie Georg Nothelfer

Britta Lumer, 2020, 16. August, 2020 (045), Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Britta Lumer, 2020, 16. August, 2020 (045), Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Britta Lumer, 2020, 19. September 2020 (098), Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Britta Lumer, 2020, 19. September 2020 (098), Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Britta Lumer, 2020, 18. September 2020 (097), Collage, Charcoal on Paper 42 x 29,7cm

Britta Lumer, 2020, 18. September 2020 (097), Collage, Charcoal on Paper 42 x 29,7cm

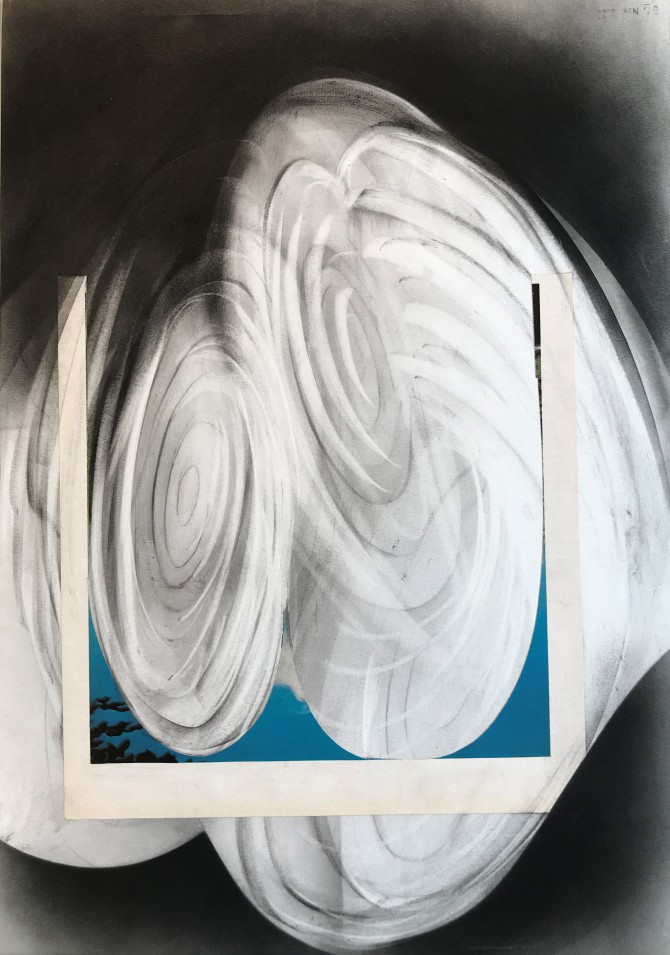

Britta Lumer, 2020, 06. November 2020 (102) Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Britta Lumer, 2020, 06. November 2020 (102) Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Britta Lumer, 2020, 15. September 2020 (099), Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Britta Lumer, 2020, 15. September 2020 (099), Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Installation view Showroom Galerie Georg Nothelfer

Installation view Showroom Galerie Georg Nothelfer

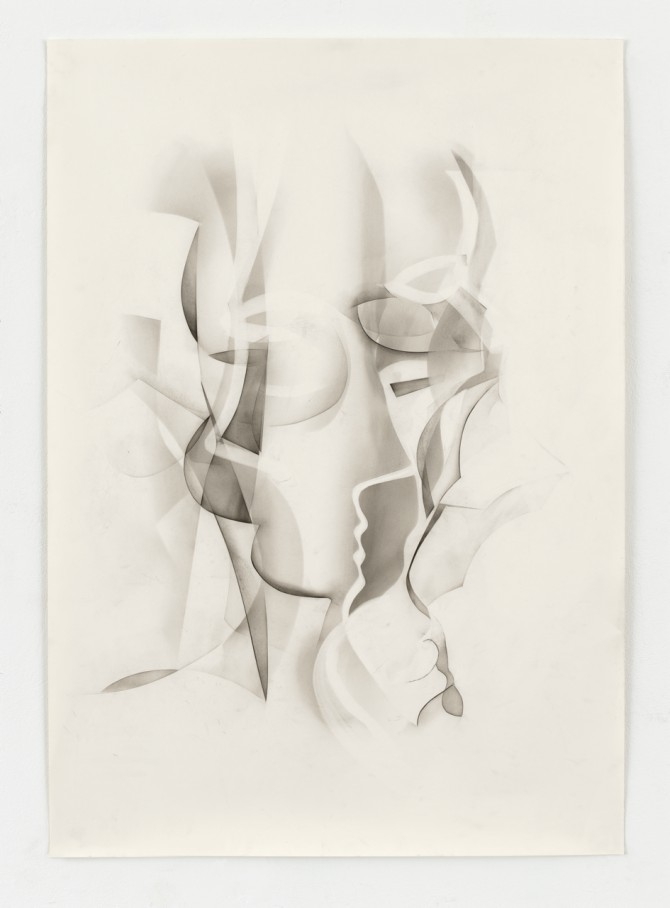

Britta Lumer, 2019, O.T. (Head 2), Charcoal on Paper, 95 x 70 cm

Britta Lumer, 2019, O.T. (Head 2), Charcoal on Paper, 95 x 70 cm

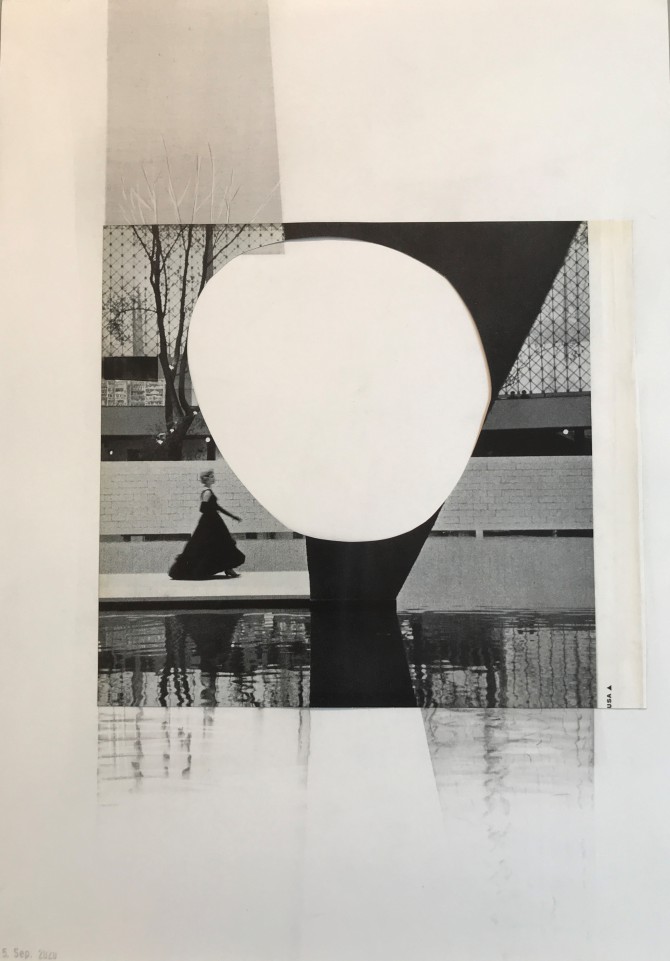

Britta Lumer, 2020, 25. October 2020 (058) ,Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Britta Lumer, 2020, 25. October 2020 (058) ,Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Britta Lumer, 2020, 20. September 2020 (047), Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Britta Lumer, 2020, 20. September 2020 (047), Collage, Charcoal on Paper, 42 x 29,7 cm

Showroom Galerie Georg Nothelfer

Grolmanstraße 28

10623 Berlin

Soft Opening July, 2 from 12 - 19h. Britta Lumer will be present from 16 - 19h.

Britta Lumer / Eduardo Chillida

Grolmanstraße 28

10623 Berlin

Soft Opening July, 2 from 12 - 19h. Britta Lumer will be present from 16 - 19h.

Britta Lumer / Eduardo Chillida

The evening moves slowly, and I, gazing, want to see.

It’s twenty years since I first visited Britta Lumer's Berlin-Kreuzberg studio-living space. Today, I made a comparable trip. Some of the street graffiti has changed – more silver-egotism, less overt politics. But her building's stairs still look and smell like 1995. Through an entrance hall lined with art materials we ended up back at her kitchen table, surrounded by her images. There are many more of them since last time: on the walls, in neat stacks, layout on tables, stored in archive boxes. We are older but that wasn't our doing. We are silent. I wait and look around. The artist makes coffee. It's sweltering. A studio practice is more than a practical or economic matter – it evidences ethics and beliefs about how art and life should get along or end in acrimony. I make a note: 'hindsight – art?' that goes nowhere. A pigeon, whose curiosity disturbed our conversation, could be a distant relation of one that squatted the neighbourhood on my first visit. Lumer shoos it away – we need space.

Through the immersive presence of her work we regroup, cohabit a ripple in 'contemporary art' spacetime. Establishing the continuum are dozens of sheets of thick paper held aloft by nifty magnets on grey walls. Charcoal, watercolour or ink haunts these images depicting moody architecture, or heads and bodies afflicted by abstract thoughts. There are angles, vectors, tonal clouds and blooms, shadows and highlights. Notional pictorial spaces multiply in her compositions. They move, flow, dissolve: tease the vagrancy of perception. They probe and prod the border territory where the recognisable and reasonable ends, or stray in the face of uncertainty.

Lumer is thoughtful, consistent and resolute. You can see and feel this in the sensitivity apparent in her works' tonal washes, the varying thickness of a line, the arch of a curve. If I lived with one of these pictures, it would be different every day. Their eyes and mouths – or what we identify as such – might move, swap places. The atmosphere would shift, the mood alter. We get interrupted. Someone telephones querying a small invoice. The artist in profile is eager to hang up, time is precious and passing. 'It's resolved... I have to go...' Lumer apologises, then summons up the image of the woman in her office engrossed in her own world of figures and papers. A life-collage, a parallel.

I ask Lumer something unintelligible concerning the role of spirituality. She answers that for a while that she studied meditation with a Zen master. Then she talks of traditional Chinese ink painting, although she couldn't imagine giving up the Western excitement for the new, the speculative in favour of the discipline of evermore refined gestural repetition. A question suggested by her work hangs between us. Is there a way to examine the self in a selfless fashion? It is too easy to get caught up in reactions and relations; discourse as art's endgame. Aesthetic experience is not just a vehicle but that which distinguishes art from ideas.

Lumer doesn't question 'being an artist'. It is something that she does. Art must be its own reward. Her work is free of cynicism, self-protective irony, chic summation, fashionable topicality or posturing. Dozens of works evidence this artistic freedom. One based on the praxis of cultivating intuition, revisiting, looking within and questioning what one might find there, acknowledging the light and the dark, the spectrum of shades in between. Her images rise to the surface, involve personal discovery. Her female heads and figures (self portraits, Ur-women?) suggest a disquieting psychological dimension, a restlessness about the status quo, maybe an implicit, non-partisan feminism, a state of flux, grappling and change. A strict, documentary colour pallet suggests an ongoing investigation, a need for a revelatory body of evidence. One that is ephemeral, not exculpatory. Her brave life choice to date to work almost exclusively 'on paper' speaks volumes. It is testament to values such as modesty and humility; a faith in authenticity, directness, and truth (or fleeting glimpses thereof). These qualities are intrinsic to the materiality of the work: paper thin as skin and allergic to acidity, archaic charcoal and granules of water borne pigment. As we talk, the artist holds up a jar containing enough colour to last a decade. 'My work is nearly immaterial,' she says.

On of the two directors of Galerie Georg Nothelfer told me she thinks we live in times comparable to the late Baroque period when art is expected to be ever more spectacular, novel, dazzling. This two-person exhibition is a welcome antidote to the fibrillating cultural compass of neo-liberal postmodernism. The exhibition's title quotes a poetic and speculative artist's text 'Questions' (1994) by Eduardo Chillida (1924-2002). Throughout his life, alongside his monumental abstract works in steel, alabaster and felt, Chillida maintained a discrete practice of refined conceptual works on paper. He considered his around 700 drawings, etchings and woodcuts not as studies for his sculptures, but complete works in and of themselves. They exist in a different dimension in every sense to his sculpture, for instance, Berlin (2000), sentinel in front of the Chancellery behind a security fence. The gallery's unlikely pairing of these two artists has an abstract rationale. The gallery with its storied history mediating postwar abstraction wishes to support intergenerational dialogue. One which in this exhibition hinges on both artists' affinity to expressing notions of space and time in two modest, concentrated dimensions.

Included in the exhibition is an excerpt from a series of Britta Lumer's collages incorporating snippets from the West German magazine 'Magnum' (1954-1966). The works were produced day by day in her studio during the period of isolation and introspection that was 2020 as we sheltered from viral infection. The magazine issues used were 'found objects' once part of an abandoned library in a countryside retreat owned by an entrepreneur with waning fortunes as well as cultural and artistic leanings which, for him, remained a promise unconsummated. Magnum magazine was once the purveyor of classy and confident postwar architecture, art, designer objects. Glossy, high-contrast, black-and-white. Lumer's father wanted to be a Magnum photographer. It was also the kind of publication that may have featured an emergent Chillida. Cultural entropy at work. In Lumer's series the now abandoned construction site of full-tilt postwar Modernism is fragmented, digested and reconfigured. In 16.08.2020, untitled (2020) for instance, the hair of a makeup and costume designer for television sprouts wavering lines like vines and waves of empathetic, experiential, trans-generational energy made visible.

His etchings suggest floor plans or diagrams – looking at them we see the weight of the printing press, the metal plate on paper, the traces of their own making. Chillida was an abstract artist but in his Esku series only superficially at odds with his own abstract orthodoxy he would return to making images of his own hands. For him, it was a part of the body that can best define space. His starting point: a thumb and index finger forming an organic circle, a porthole. The active space of materiality along with negative space redolent, not of a void, but of opening up to a horizon.

Text: Dominic Eichler