Manfred Hamm. Berliner Mauer

15 November 2014 to 10 January 2015 ⟶ Corneliusstraße

Exhibition view

Exhibition view

View from the Reichstag, 1986, colour photograph, Aufl. III, 120 x 160 cm

View from the Reichstag, 1986, colour photograph, Aufl. III, 120 x 160 cm

Wedding, death strip on Liesenstraße, 1976, 40 x 30 cm unique and 2014 as edition, edition V

Wedding, death strip on Liesenstraße, 1976, 40 x 30 cm unique and 2014 as edition, edition V

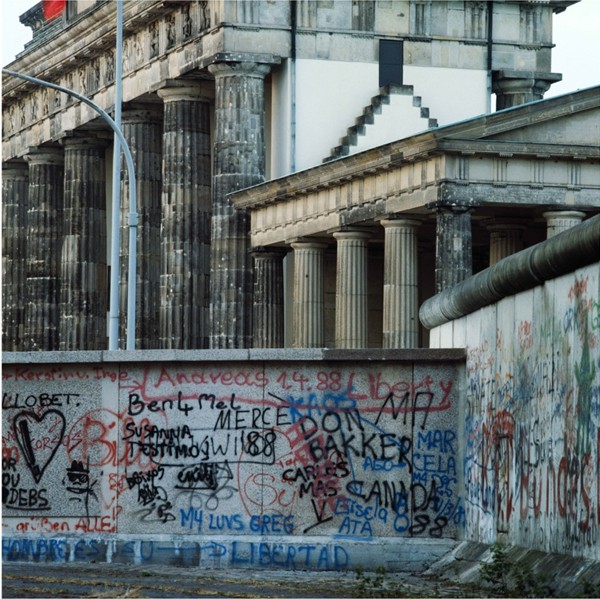

Brandenburg Gate, 1989, colour photography, ed. III, 140 x 140 cm (SOLD)

Brandenburg Gate, 1989, colour photography, ed. III, 140 x 140 cm (SOLD)

Brandenburg Gate, view from the Reichstag, 1986, colour photograph, unique piece, 120 x 100 cm

Brandenburg Gate, view from the Reichstag, 1986, colour photograph, unique piece, 120 x 100 cm

Brandenburg Gate, 1988, colour photograph, unique piece, 120 x 120 cm (SOLD)

Brandenburg Gate, 1988, colour photograph, unique piece, 120 x 120 cm (SOLD)

Exhibition view

Exhibition view

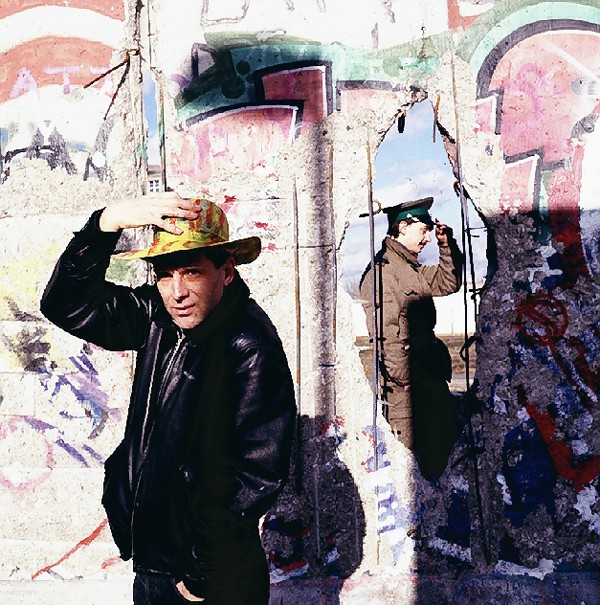

Rainer Fetting in front of the Wall, 1990, colour photography, Aufl. V, 140 x 140 cm

Rainer Fetting in front of the Wall, 1990, colour photography, Aufl. V, 140 x 140 cm

Berlin Tiergarten, The Fall of the Wall, 1989, b/w photograph, unique piece, 25 x 36 cm

Berlin Tiergarten, The Fall of the Wall, 1989, b/w photograph, unique piece, 25 x 36 cm

Vopo (GDR policeman) in the death strip, 1976, b/w photograph, unique specimen, 30 x 40 cm

Vopo (GDR policeman) in the death strip, 1976, b/w photograph, unique specimen, 30 x 40 cm

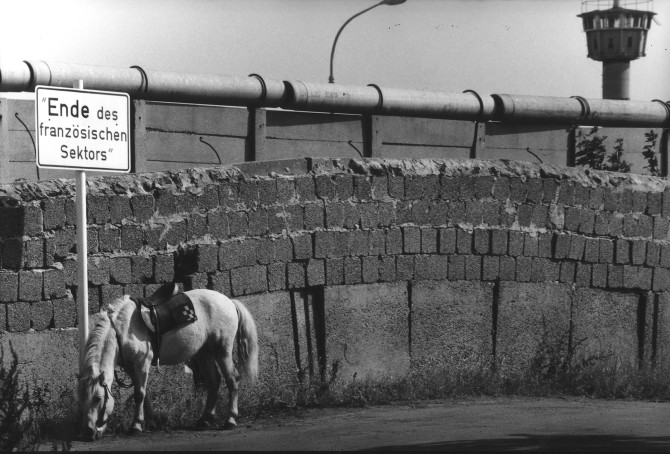

Berlin Wall - French Sector/Märkisches Viertel, 1976, b/w photograph, 1st print, 30 x 40 cm

Berlin Wall - French Sector/Märkisches Viertel, 1976, b/w photograph, 1st print, 30 x 40 cm

At Potsdamer Platz, in the background Haus Vaterland, 1976, b/w photograph, unique piece, 30 x 40 cm

At Potsdamer Platz, in the background Haus Vaterland, 1976, b/w photograph, unique piece, 30 x 40 cm

View from the Reichstag, 1986, b/w photograph, unique piece, 30 x 40 cm

View from the Reichstag, 1986, b/w photograph, unique piece, 30 x 40 cm

Enclave Steinstücken, 1972, b/w photograph, unique piece, 30 x 40 cm

Enclave Steinstücken, 1972, b/w photograph, unique piece, 30 x 40 cm

Exhibition view

Exhibition view

View from the Reichstag, 1986, colour photograph, Aufl. III, 120 x 160 cm

View from the Reichstag, 1986, colour photograph, Aufl. III, 120 x 160 cm

Photographs 1972-1990

Manfred Hamm actually wanted to photograph Theodor Fontane's grave. In December 1976, the photographer was standing on Liesenstraße in the West Berlin district of Wedding, the grave site in the cemetery of the French Reformed Parish was not far away. But an insurmountable obstacle blocked Hamm's way: the death strip of the Berlin Wall. Suddenly, however, another motif hopped into his picture. A hare sat down on the lawn. He pulled the trigger: In front, the peaceful animal poses, in the background are the tank barriers of this heavily guarded border. If a human had entered the death strip instead of the hare, his life would have been in danger. "Here in the GDR, every child knows that the border troops have strict orders to shoot people as if they were rabbits," ARD correspondent Lothar Loewe had said shortly before on the Tagesschau - and had promptly been expelled from the GDR. "'Shooting people like rabbits' just popped into my head when I took the photo," says Manfred Hamm. Over the years, the photographer documented the inner-city border and life around it with numerous pictures. "I always wanted to become an ethnologist," he recalls. "But a professor warned me: you are a romantic. Do something else." So the budding chronicler of the Wall went on expeditions inland as a photographer instead. "I walked the entire Wall around Berlin," Hamm says. In stages, he completed the roughly 160 kilometres. This required creativity. For example, Hamm did not get permission to visit the West Berlin exclave of Steinstücken, which was encircled by the GDR. So the US army flew the West Berliner there as a press photographer. "I was never alone, of course; I was always being watched with binoculars from the nearest watchtower," he says, describing his experiences in the border area. "It was a mutual observation. The border guards probably took more photos of me than I did of the Wall." When the Wall fell in 1989, Hamm commented on the event with the phrase "Today's junk is tomorrow's archaeology". He now documents the disappearance of the "anti-fascist protective wall" with his photos in the exhibition "The Wall" in Berlin. "The Wall has always reminded me of a kind of stage set," says Hamm. He felt that the colourfully painted Wall on the death strip was a backdrop in front of which the inhabitants played as protagonists in an absurd play called Contemporary History: In his photographs, artists pose in front of the Wall, horses and rabbits conquer the death strip, soldiers peer over curiously. In July 1990, the sculptor Rainer Fetting placed his sculpture "The Flight" in front of a hole in the Wall at the Martin-Gropius-Bau. Hamm took more than 500 photos over the course of 24 hours, and at night he pointed a huge spotlight at the figure. "The whole time our production was being gawked at from the watchtower," says Hamm: "What director has such a loyal audience?" In Hamm's pictures, the Wall at the time of the Cold War usually seems less threatening than helpless, absurd, bizarre. He subversively undermined its threatening intimidation. Once, when he photographed Rainer Fetting in front of a hole in the Wall in the summer of 1990 with his hand on his hat making an Udo Lindenberg gesture, he asked the Volksarmist in the background to please make the same move: "To our surprise, he really did that." By then, however, the Wall had already fallen. (Text: Hilmar Schmundt)

Manfred Hamm actually wanted to photograph Theodor Fontane's grave. In December 1976, the photographer was standing on Liesenstraße in the West Berlin district of Wedding, the grave site in the cemetery of the French Reformed Parish was not far away. But an insurmountable obstacle blocked Hamm's way: the death strip of the Berlin Wall. Suddenly, however, another motif hopped into his picture. A hare sat down on the lawn. He pulled the trigger: In front, the peaceful animal poses, in the background are the tank barriers of this heavily guarded border. If a human had entered the death strip instead of the hare, his life would have been in danger. "Here in the GDR, every child knows that the border troops have strict orders to shoot people as if they were rabbits," ARD correspondent Lothar Loewe had said shortly before on the Tagesschau - and had promptly been expelled from the GDR. "'Shooting people like rabbits' just popped into my head when I took the photo," says Manfred Hamm. Over the years, the photographer documented the inner-city border and life around it with numerous pictures. "I always wanted to become an ethnologist," he recalls. "But a professor warned me: you are a romantic. Do something else." So the budding chronicler of the Wall went on expeditions inland as a photographer instead. "I walked the entire Wall around Berlin," Hamm says. In stages, he completed the roughly 160 kilometres. This required creativity. For example, Hamm did not get permission to visit the West Berlin exclave of Steinstücken, which was encircled by the GDR. So the US army flew the West Berliner there as a press photographer. "I was never alone, of course; I was always being watched with binoculars from the nearest watchtower," he says, describing his experiences in the border area. "It was a mutual observation. The border guards probably took more photos of me than I did of the Wall." When the Wall fell in 1989, Hamm commented on the event with the phrase "Today's junk is tomorrow's archaeology". He now documents the disappearance of the "anti-fascist protective wall" with his photos in the exhibition "The Wall" in Berlin. "The Wall has always reminded me of a kind of stage set," says Hamm. He felt that the colourfully painted Wall on the death strip was a backdrop in front of which the inhabitants played as protagonists in an absurd play called Contemporary History: In his photographs, artists pose in front of the Wall, horses and rabbits conquer the death strip, soldiers peer over curiously. In July 1990, the sculptor Rainer Fetting placed his sculpture "The Flight" in front of a hole in the Wall at the Martin-Gropius-Bau. Hamm took more than 500 photos over the course of 24 hours, and at night he pointed a huge spotlight at the figure. "The whole time our production was being gawked at from the watchtower," says Hamm: "What director has such a loyal audience?" In Hamm's pictures, the Wall at the time of the Cold War usually seems less threatening than helpless, absurd, bizarre. He subversively undermined its threatening intimidation. Once, when he photographed Rainer Fetting in front of a hole in the Wall in the summer of 1990 with his hand on his hat making an Udo Lindenberg gesture, he asked the Volksarmist in the background to please make the same move: "To our surprise, he really did that." By then, however, the Wall had already fallen. (Text: Hilmar Schmundt)